I met Vivek Shraya on February 1, 2003, upstairs at Remedy Cafe on 109th Street in Edmonton. I was already a fan of his music, thanks to a copy of Samsara: The Sketches I’d bought from my college classmate (and Vivek’s brother) Shamik, but I’d never made it out to one of Vivek’s gigs. This was his last hometown show before he moved to Toronto—

The show was terrific. Shamik introduced us afterward, and I did my best to act cooler than the shy and slightly star-struck 18-year-old I was. Somehow I even found the nerve to tell Vivek I made websites, and if he wanted one, he should get in touch.

A few weeks later, he did just that. By April, we had a site up. And before long, in a flurry of emails and LiveJournal posts and MSN Messenger conversations, we’d become friends. Nearly 12 years, five albums, three books, four short films and at least eight websites later, I still count Vivek as one of my dearest friends.

His new book is called She of the Mountains. It’s about love, love as a verb, in all its terrifying complexity, all its intersections with need and worth and ownership and identity. I bought a copy as soon as I could, read it in one evening, finished it with tears in my eyes. It’s a book with a lot to say, and I found I had a lot I wanted to say back.

S.C. First off, congratulations on the release! Reviews are coming in, you had the launch party last week, and now you’re heading out on a huge reading tour, including several dates with the ladies from Everyone is Gay. How do you feel about the response the book has been getting so far?

(photo by Karen Campos Castillo)

V.S. The response has been mostly positive and I am quite relieved. I have worked longer and harder on this project than any project, so the level of investment is high. Consequently, I have been having regular anxiety dreams for the past two months. The best part about waking up the day after the Toronto book launch was the absence of that apprehensive feeling.

S.C. She of the Mountains is your third book, but your first to debut from Arsenal Pulp Press. Has working with a publisher been any different from your experiences self-publishing?

V.S. Being published doesn’t feel drastically different because I am still doing much of the same kinds of leg work. What has been wonderful about working with Arsenal is that for the first time in my artistic career, I have help—

S.C. Have you noticed any differences between coverage in the mainstream press vs. coverage in queer media?

V.S. The book hasn’t received a lot of mainstream coverage yet, and again, the response from gay media has been positive, which I am grateful for. But there has been a consistent misreading of the book being about “a gay man who falls in love with a woman” and/or “someone who is struggling with their sexuality.” At some point, the protagonist certainly self-identifies as gay, but this is directly as a result of his experience of being repeatedly told he is so. It is an act of submission. I worry how and why this is being lost. The struggle is not so much about someone struggling with their sexuality, but rather someone struggling with what he is being told his sexuality is. I understand how it’s possible to conflate the struggles, but they are very different.

The struggle is not so much about someone struggling with their sexuality, but rather someone struggling with what he is being told his sexuality is.

S.C. It was incredibly powerful for me to read about that struggle—

And it gets into you, doesn’t it? Hearing over and over and over again that your sexuality is invalid, or suspicious, or subject to someone else’s review—

V.S. What has reclaiming “bisexual” involved for you?

S.C. A big part has just been using it. I’m a technical writer at my day job; precision in language is important to me. I love being queer—

Your unnamed protagonist in She of the Mountains feels too gay to be straight, and too straight to be gay, and—

V.S. Despite coming into a bisexual identity, I have found myself most comfortable in the word queer because of its openness, its undefinability and the ways it speaks to not only a fluid sexuality, but a fluid gender. Owning queer has become a way to respond to the misogyny inherent in the homophobia I have experienced. And so, in thinking about the protagonist and his experiences, queer again made the most sense.

That said, if I am being honest, my own initial reaction to the word bisexual was not unlike yours, and at its core, biphobic. I remember being about 20 years old and going for dinner with you and your then-girlfriend, who proudly identified as a bisexual Wiccan. I left that dinner thinking I was definitely not bisexual—

S.C. It’s hard to be comfortable with something in other people when you’re not comfortable with it in yourself. My first, instinctive reaction to hearing someone identify as bi is still to cringe a little—

V.S. I find myself wondering if the story would have been more effective if the protagonist identified as bi. Were you disappointed that he didn’t?

S.C. A little. I saw so much of myself in the protagonist that I wanted him to be at the same point in his journey that I was in mine. Which was irrational of me, but it speaks to how absorbed I’d become in the story. I’d also recently read Shiri Eisner’s Bi: Notes for a Bisexual Revolution, and it got me all fired up about—

V.S. I wrote this book for men like you and me. But I was thinking less about representation, and more about how to challenge the kind of biphobia I have experienced. I felt that the only way to do this was to write a bi/queer love story, one that the reader would hopefully fall in love with.

S.C. A lot of the biphobia your protagonist faces comes from inside the queer community, which felt sadly consistent with my own experience. Maybe I just expect less from straight people, but it always seems to hurt more coming from gay men and lesbians. And the scenes in your book are hurtful. Were those based on real life?

V.S. Every biphobic statement in the book was closely derived from my own experience. This felt necessary to document, if only as a form of catharsis, because of how painful and pervasive biphobia has been in my life.

S.C. There’s a quote by Ayesha Siddiqi I think about a lot:

“Be the person you needed when you were younger”.

You’ve written

two

books

about young queer men of colour, made

a film

about racism and shadism in the gay (white) dating scene, and started a

film/book/blog

project called What I LOVE about Being QUEER. What if you’d had access to media like that when you were younger? Do you think about the impact your work could make—

V.S. A major component to why I create is thinking about the kinds of resources, supports and visibility I could have benefited from as a teenager. This is why positive responses from queer youth, and youth of colour are the most meaningful responses.

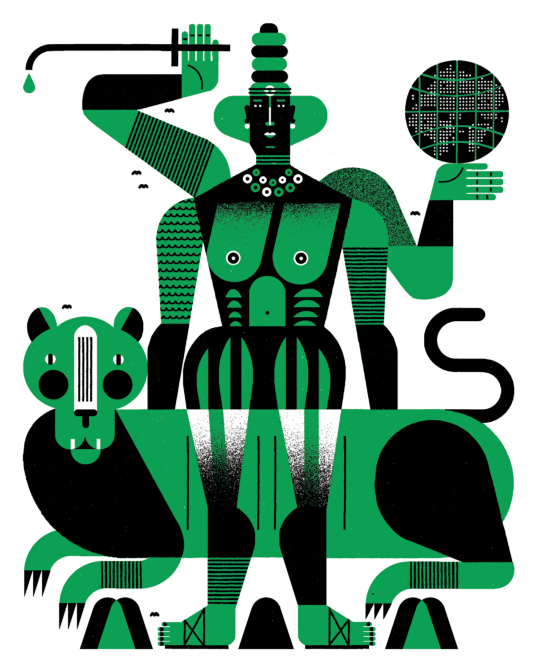

S.C. The other story in She of the Mountains is about Parvati and Shiv, and their son Ganesh. One of my favourite things about the book is the way the Hindu mythology and the contemporary story parallel each other thematically, without ever feeling forced or false. Did you always plan to tell these two stories together?

V.S. The original draft of the book was the love story and a chapter called “Parvati’s Song” (which is now the first mythological section in the book). On its own, the love story felt lacking, and I had no idea how it could fit. During the feedback process, there was consistent excitement for “Parvati’s Song,” and I decided to see how I could build upon it. The creation of Hindu god Ganesha, the basis for “Parvati’s Song,” is a story I had heard growing up, but what happened after he was born? This question and curiosity inspired the development of the mythological narrative.

S.C. How did you choose which stories to include in the mythology narrative? And how did it feel, taking these stories you grew up with and re-telling them in such an unorthodox context?

V.S. One of the unexpected turns in the writing process was that in writing about love for another, it felt important to discuss the relationship to hate and how the experience of hate embeds itself within the body, creating a sense of disembodiment. In thinking about bodies, I recalled various instances in Hindu mythology of how different gods and goddesses are created, and these stories of divine embodiment—

Because I grew up with Hindu beliefs and am grateful for the safety, imagination and love those beliefs fostered, it was important to re-tell the myths with care.

S.C. There are a lot of different kinds of love in She of the Mountains—

V.S. Thank you for saying that. I think the resistance to the old cliché, the reason why it sometimes induces an eyeroll, is that it places the responsibility solely on the individual, which can feel like blame: “Just love yourself, already!” In this “love yourself” model, there is no consideration for barriers like trauma and violence that prevent us from loving ourselves. This is why both narratives in the book begin with an account of trauma.

The other cliché worth reexamining is that love is the ultimate goal or necessity, and the ultimate healer. It is hard to admit, but I have experienced love as pain at times, because of my inability to see in myself what my partner sees, my inability to love the parts of myself they are able to love. I couldn’t write a love story about love for another without showing how love, the greatest and most abundant love, is sometimes not enough, how it falls short if you aren’t able to love yourself.

S.C. Vivek, thank you so much. This was a lot of fun. See you on Thursday!